Growing water crisis in Borrego

Years of overdrafting from underground aquifer have state pushing for community action to restore sustainability

The water crisis in Borrego Springs is as simple to understand as it will be difficult to solve.

The elephant in the room is farming.

Citrus and palm ranches in northern Borrego Springs are sucking huge amounts of water from the underground lake beneath their land — far more than the state is likely to allow in the future.

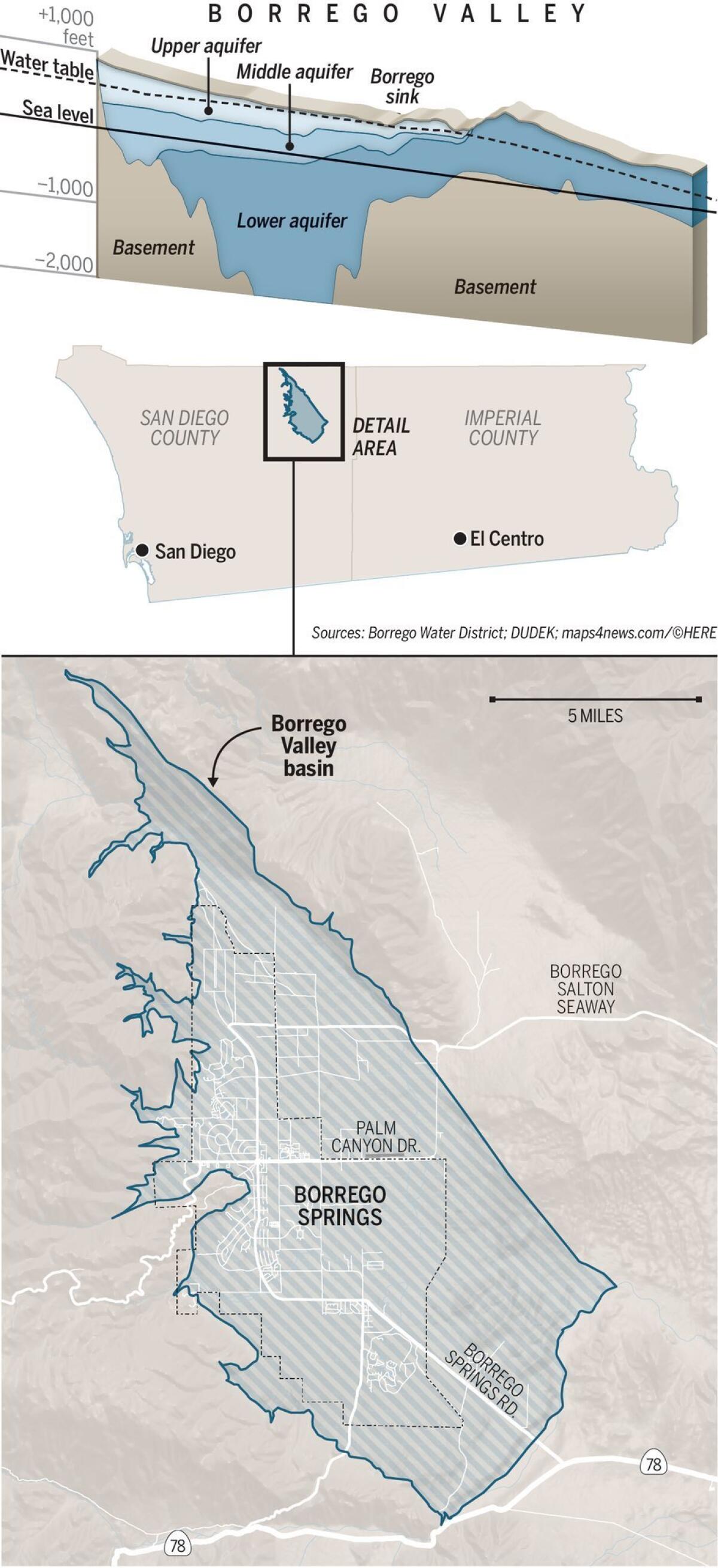

The problem: Borrego Springs, home to about 3,000 permanent residents in the desert of northeast San Diego County, has no feasible way to import water. It relies completely on an underground aquifer that on average is replenished by nature each year to the tune of about 1.8 billion gallons.

But for decades, the amount of water that has been pumped out of the aquifer has been far greater — most recently, 6.1 billion gallons annually.

IN DEPTH: TROUBLE AT THE WELL

The result of years of overdrafting in the Borrego Valley has caused the water table to drop by as much as 119 feet in some areas, including a 26-foot decline in the past decade.

It’s not that Borrego Springs is running out of water. There are, in fact, three aquifers beneath the valley, one atop the other. But as the water table drops, it becomes more and more expensive to pump water out of the ground. If nothing is done, the cost of pumping the water will eventually exceed any economically feasible rationale to continue living there or working the land.

For comparison’s sake, the city of Poway, home to nearly 50,000 people and hundreds of businesses, distributes a bit more than 4 billion gallons of water to its users annually. Borrego pumps 50 percent more water than that, even though its population is minute in comparison.

In the northern part of town are farms, roughly 2,000 acres of grapefruit, lemons, tangerines, tangelos and palm trees.

Many of the farms have been in operation for more than half a century and all have clear rights to the water beneath their land. The farms use 70 percent to 80 percent of the water pumped out of the ground.

The rest is consumed by five golf courses, resorts and residents, most of whom get their water from pumps controlled and distributed by the Borrego Water District.

Sustainability plan

It’s been known since the early 1980s that an overdraft problem exists. Comprehensive studies have put hard numbers to the staggering issue.

What has changed recently is a threat from the state, which last year enacted laws aimed at communities that rely on underground water.

There are more than 500 such sole-source basins in California, including 127 that have been determined to be of medium and high priority.

Borrego is placed in the medium category not because its problem isn’t immense, but because relatively few people are affected. More important, the Borrego Valley has been designated to be in “critical overdraft,” one of only 21 basins in the state (most are in the Central Valley) and the only one south of Los Angeles.

The state is demanding that the community — in this case it will be the Borrego Water District in conjunction with the County of San Diego — come up with a plan by 2020 to bring the basin into sustainability. If no plan is promulgated, the state will take over.

“You know the saying, ‘I’m here from the government. I’m here to help you.’ That’s usually not a good thing,” Borrego Water District General Manager Jerry Rowling told a town hall gathering in late March.

The plan must then be implemented and progress has to be shown up until 2040, by which time the amount of water being pumped out of the ground can be no greater than what is naturally recharged.

During the town hall gathering, Borrego Water District President Beth Hart was asked what the chances are that farmers will cut back usage to anywhere close to the levels that will be needed.

“I wouldn’t have had a good answer three years ago,” Hart said.

That was when the Department of Water Resources drew together a group of the largest pumpers in the basin — farm owners, golf course heads, state park representatives, local business owners and residents — a group that eventually called itself the Borrego Water Coalition.

Hart said initially the farmers’ positions were intransigent.

“What we initially heard was that no one was going to do anything except sue somebody else,” she said. “But what we found after talking with them is business people — business people (who want to either) continue their business or make themselves an exit strategy that would work.”

She said the farmers can see the reality. Because of the new water sustainability rules, they will either have to leave the valley or find some way to sell their crops at high enough prices to cover the costs.

The district has already been approached by nonprofit land acquisition and environmental groups that are waiting to see if an opportunity arises, Hart said.

Borrego Springs is surrounded by the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. The Anza-Borrego Foundation, which for decades has been purchasing land to add to what is by far the state’s largest park, is one of those groups.

“We certainly know how to do it,” said Paige Rogowski, the foundation’s executive director. “This would be new territory for us specifically with agriculture land. But if we can work it out, we’re glad to help.”

Wealthy part-time residents with vacation homes in the area and their own foundations have also expressed willingness to help with the problem, Hart said.

One idea in its infancy could involve UC Irvine, which has a desert research station in the area.

“They are interested in taking farmland that is fallowed and seeing what it would take to restore it,” Hart said recently. “I don’t know if that’s anything more than an idea at this point, but it would certainly be a wonderful opportunity for folks in the valley to figure out what it would cost, how it would work, whether its doable and putting an academic aspect to it.”

Hart said there is also a question of whether the park system would want fallowed farmland.

“The park historically has not wanted disturbed property. They prefer property that is native or can be put back in a fairly inexpensive way. I’m not quite sure if any of us have an answer about how everything is going to happen when it comes to the fallowed properties,” she said.

It will also be difficult to get donations to buy farmland until the legal ramifications of the new rules, and challenges to any sustainability plans, have been litigated, presuming such challenges are forthcoming. Donors are less likely to give cash to buy land if the threat of litigation might consume those funds in legal fees.

Other options include people buying a farm, fallowing it, and then using a fraction of the water credits for their own projects. Such is how the recently reopened Rams Hill Golf Course got permission to turn its pumps back on.

Farming’s role

At the northern terminus of Borrego Valley Road sits Seley Ranch where Rio Red grapefruit and lemons, among other citrus products, have been grown on 376 acres since the late 1950s.

Jim Seley is active in the water coalition and has implemented water-saving techniques in recent years.

Ryan Fancy, the ranch manager, takes pride in what is being grown. As he cut into a grapefruit and squeezed, he said the Seley fruit is shipped all over the world.

“We’re not watering grass,” he said. “We don’t have 50-foot sprinklers shooting up in the sky to water a golf course nobody golfs on four months of the year (when Borrego Springs is all but shut down because of summer heat).

“We’re feeding people here!”

Fancy talks about the intricate irrigation methods that make sure each tree receives just the right amount of water without any being wasted. He shows how detection devices allow him to monitor on his cellphone exactly what the weather and moisture levels of the ground are at any given moment. Seley can follow along on his computer in his Pasadena office.

The ranch recently installed filtration backwash equipment from Israel, which flushes sediment from the water being pumped using less than one gallon instead of hundreds each time. And workers are constantly repairing leaking pipes and malfunctioning sprinklers, Fancy said.

They use “micro-jet” sprinklers Fancy calls super-efficient. “With frequent shallow irrigation you’re just putting a little bit of water on every other day. And you’re targeting exactly where your root zone is.”

Still, the ranch — indeed all the farms — use a great deal of water.

There are three active pumps on the Seley ranch property. Each draws about 1,700 gallons a minute from the earth. On average, each pump is run 10 hours a day — less in the cooler winter months, much more in the summer.

That’s more than 1 billion gallons of water annually.

Seley recently said he’s not convinced the overdraft figures are accurate, and as farmers and others start to reduce consumption during the first part of the sustainability plan, he will be eager to see what happens to water levels.

“It’s still an art and not a science yet,” he said.

Seley and others said the overdrafting has slowed as farmers and others have put conservation techniques into practice.

Right now, the farmers are being told they will have to cut back on their operations 70 percent by 2040. But he said that figure could go up or down once the plan is in place.

He said he expects some farm owners will give up, tired of the fight and fed up with rising electricity costs to power their wells. He said he would expect to see a 20 percent reduction in farming in five years and maybe another 20 percent in 10 years.

There will also be regulatory pressure in the form of fees and fines.

Under the sustainability rules, the water district/county group that will oversee the plans will have the power to force farmers to install meters on all pumps to know exactly how much water is being used. Then a reduction schedule will be established and if the goals aren’t met, fines will be levied.

End isn’t near

Hart told the town hall gathering that there are some in Borrego Springs who think time is running out, that its water problems are insurmountable and the town may simply cease to exist.

“That is not how this board views are current circumstances,” Hart told the gathering. “Instead, our message is one of hope along with a realistic approach that says, it’s not going to be easy, but it will be worth it.

“… Instead of waiting for the state or some other governmental agency to apply a ‘one-size-fits-all’ remedy for the overdraft with little or no consideration as to the local reality that is here, we are working to retain local control, address local issues and create practical resolutions to local problems.”

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.