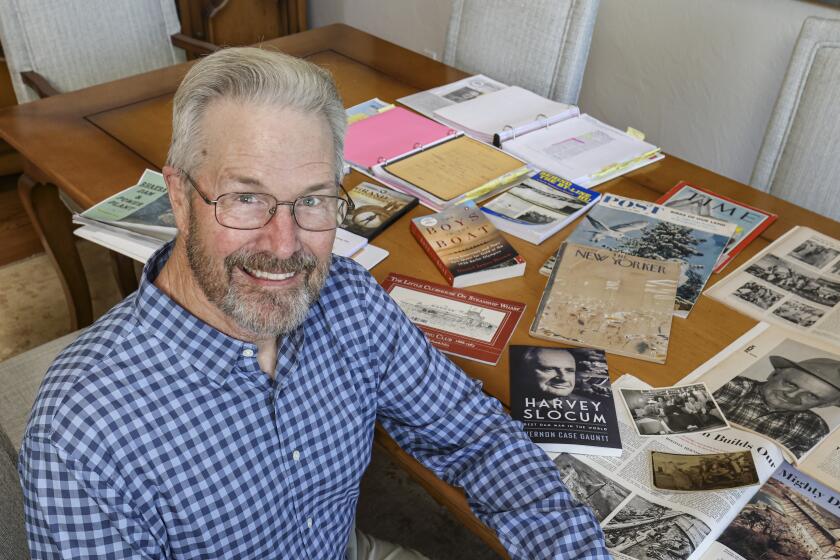

Debut novelist gives the voiceless a voice

The title character in “The Invisible Life of Ivan Isaenko,” San Diego writer Scott Stambach’s debut novel, is a 17-year-old boy living in a Belarus hospital for “gravely ill” children.

“My body is horribly incomplete,” Ivan notes early on: no legs, one arm, and a hand that’s missing two fingers. The muscles in his face droop, “which makes me look like an idiot.” But his mind is sharp, his tongue even sharper, and in a world where every day is the same, he survives by playing tricks on other people and by imagining he’s someone else: Spartacus, the Dalai Lama, Eminem.

Then a smart girl with cancer named Polina arrives, and Ivan dares to hope for something more.

Stambach, 36, teaches physics at Mesa and MiraCosta colleges. He’ll be at Warwick’s at 7:30 p.m. Sept. 8.

Q: How does someone who teaches college physics also turn out to be a novelist?

A: I don’t know. I just feel grateful that whatever that is that it takes to be a writer apparently I have. Part of what I love about writing so much is that it is a really mysterious thing.

Q: How long have you been doing it?

A: About the last 10 years, ever since I read the novel “House of Leaves” by Mark Danielewski. If you flip through it, you will see it is just the most wild, creative, amazing thing, and when I finished it I was like, “Oh, my God, I want to do this. I want to make somebody feel how I just felt reading this book.”

I started writing short stories and trying to get them published. I was getting rejected all the time but working at it every day, trying to hone my craft. One of those short stories got the attention of an agent, Victoria Sanders, who said, “This should be a novel.” When you’re not published, you listen to what agents ask you to do.

Q: Did you study writing in college?

A: I took one creative writing class at UC San Diego.

Q: I understand the idea for this book started with a documentary you saw about Chernobyl (site of a catastrophic nuclear power plant accident in 1986). What was it about that movie that grabbed you?

A: So much. More than anything, it’s the fact that in the world there can exist places where human beings live who have all the same urges and dreams and instincts and desires that other human beings have, and yet through no fault of their own they have no ability to realize them. That kind of suffering, and the fact that it seemed so hidden, haunted me.

The whole idea of Chernobyl haunts me, but this kind of brought it home, put faces to it. I started flirting with the idea of what it would be like to give one of those kids a voice. What would that sound like if you were raised in that environment? How would you cope? What would your defenses be and what would your chances be for real, genuine connection with other people? This book is that experiment.

Q: Why was it important to you to give a voice to the voiceless?

A: The human condition is a really interesting thing to me. On one level, I think this book is kind of a metaphor for all of us in the sense that no matter how confident we portray ourselves, any human being I’ve ever met holds inside this image of somehow being broken and somehow being deformed and somehow not being worthy of love and connection. There is this kind of voice that plays out in our heads.

The hospital is a metaphor for the little children inside our own heads who tell us all this stuff and struggle to feel worthy. So in one sense it’s important to me because it calls attention to this thing that we don’t really talk about but I think is a common human impulse or habit.

Also, there is something about disability and things that are wildly different that is deeply uncomfortable to us. And because of that I think we let ourselves lose the humanity in it because we don’t want to touch it, we don’t want to look at it for too long. Not because we’re evil, not because there is anything wrong with us, but just because we’re not used to dealing with that kind of emotion.

In a big way, this book forces us to look at it, including me. I’m no exception. It’s awfully hard to really get in touch with the humanity in people who are different — the disabled, the homeless, people who are mentally ill. Humanity runs just as rich in those folks as it does with us.

Q: In giving him a voice, how much of Ivan is you? I’m thinking in particular about the humor and the sharp observational skills.

A: It’s funny you ask that question. I usually tell people it’s 60 percent. I actually put a number to it.

Q: Well, you are a scientist.

A: I would say there’s definitely an overlap there in my inner child and Ivan.

Q: I asked because some writers wish they could be that quick in real life, which is why they write their characters that way. Ivan doesn’t have the filter a lot of us would consider important in our exchanges with people.

A: Exactly. I do have that filter. I would say that the 40 percent of him that is not me is the part that’s a complete (expletive).

Q: Ivan is someone who has spent his whole life in the hospital so he has no experience with the outside world. How were you able to create that world and turn off what you already know?

A: Every morning when I got up at 5 to write, I literally put him on. I wore him. I tried to embody what this kid would be like and I put myself in the hospital. There was nothing conscious about cutting off what I knew about the world. It would bleed in through some pop culture references, which I think are kind of fun. The television in the hospital’s main room — that was my window to letting outside things seep in. But I didn’t specifically try to let go of the real world. I specifically tried to inhabit him.