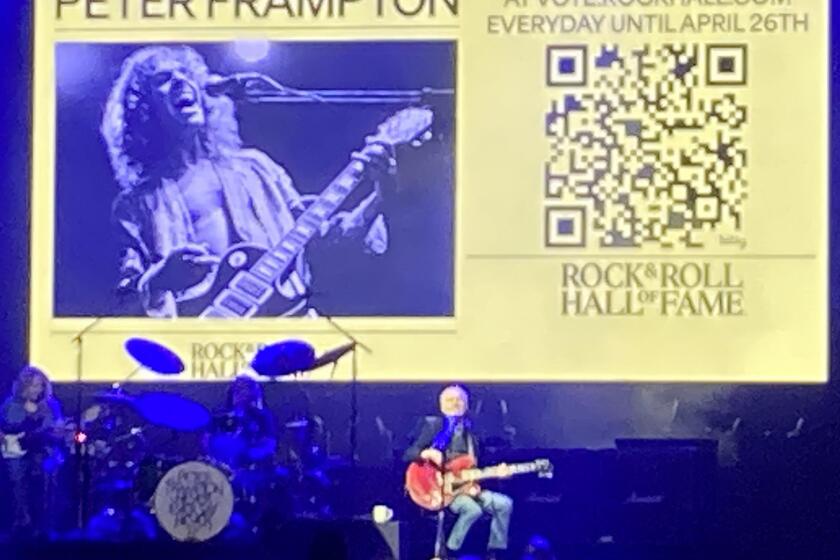

Gregory Porter reflects on music, football & destiny

The former SDSU football lineman-turned-Grammy-winning-vocal-star owes his singing career, in large part, to painful football injury.

Hindsight being 20/20, suffering a career-ending football injury at San Diego State University is one of the best things that ever happened to Grammy Award-winning singer Gregory Porter.

A gentle giant with a deep, wonderfully supple singing voice and the ability to fuse genres with ease, Porter stands 6-foot-4 and weighs 255 pounds. Barely three months after enrolling at SDSU in January 1990, where he had earned a full, four-year scholarship, the Bakersfield native was injured during spring practice.

The hulking lineman, who performs with his band next Saturday, May 7, at Jacobs Music Center’s Copley Symphony Hall, never returned to the football field. He has, however, sang at such historic venues as the Hollywood Bowl and London’s Royal Albert Hall, and this summer headlines or co-headlines at leading jazz festivals around the world.

Gregory Porter

with the Gilbert Castellanos Quintet, featuring Marshall Hawkins and Joshua White, presented by Jazz @ The Jacobs

When: 8 p.m. next Saturday, May 7

Where: Jacobs Music Center’s Copley Symphony Hall, 750 B St., downtown

Tickets: $20-$65

Phone: (619) 235-0804

Online: sandiegosymphony.com

“I had a torn right rotator cuff,” said Porter, 44. who briefly played — or, more precisely, practiced — here alongside future NFL star Marshall Faulk. “I don’t want to say I was doubly injured because of physical therapy, but I was never able to get my shoulder strong enough again.”

Porter was understandably devastated.

“I remember standing in my apartment in San Diego, boohooing. But it turned out great. I think my mother saw the positive side of my injury before I did,” he recalled. “My mother said, ‘Now you have more flexibility to explore music, focus on your studies and see what happens.’

“I think every person who gets a football scholarship thinks the potential for great success in college — and maybe even a career in the NFL — is possible. But I think I ended up in the right place.”

He certainly did.

San Diego mentors

During an in-depth phone interview last week from London, Porter reflected on the ultimately fortuitous aftermath of his football injury.

He was on tour in Europe, where he is an established star, to promote his fourth and newest album, “Take Me to the Alley.” Due for release here by Blue Note Records on Friday, it’s the sublime follow-up to his million-plus-selling “Liquid Spirit,” which earned him a 2014 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Vocal Album.

Deftly drawing from jazz, gospel, R&B, pop and more, “Take Me to the Alley” is the best showcase yet for his carefully crafted lyrics and mellifluous baritone vocals. Without compromising his artistic integrity in the slightest, Porter has made an album that could appeal to a broad range of listeners beyond jazz fans, just as he has already done throughout much of Europe.

His velvety singing at times suggests an enchanting musical confluence of Nat “King” Cole, Bill Withers, Johnny Hartman and Joe Williams, mixed with a fresh, vital style that is uniquely Porter’s own. That multifaceted style can be traced largely back to his time here following the torn rotator cuff injury that changed his life.

With football behind him, Porter began exploring other options. Already an experienced gospel singer, he began delving into this city’s then-small but vibrant jazz scene.

He befriended San Diego jazz patriarch Daniel Jackson, who became a key early mentor. So did University of California San Diego music professors Kamau Kenyatta and George Lewis, who now heads the jazz studies department at Columbia University in New York, and trumpeter Gilbert Castellanos, who in the mid-1990s became one of the most active jazz performers and jam session leaders in town.

“George heard me at a jam session,” Porter recalled. “He said, ‘I know you’re not enrolled at UCSD, but come to my class anyway.’ The third or fourth time I did, George wasn’t there and Kamau was substitute-teaching. Kamau said: ‘Let’s help you out. Let’s develop your repertoire.’ And he really did. He was so encouraging and shared so much with me.

“They were all instrumental for me. When they see a young artist with raw talent, they encourage them. That’s what George, Daniel, Kamau and Gilbert did. Daniel would laugh, and say, ‘You don’t even know what you have!’ And Gilbert would cuss at me, in a good way: ‘(Expletive), you need to be heard!’

“And I was like, ‘OK!’ Because I idolized Gilbert; I did and do. I built my jazz foundation in San Diego for sure. To this day, I do (Nat Adderly’s) ‘Work Song’ at nearly all my concerts, and that’s a song I first started doing with Gilbert in San Diego.”

Like few vocal artists today, Porter’s delightfully resonant combines smoldering gospel passion with urbane jazz sophistication to create a soulful sound that, in Europe, has seen him score Top 10 pop hits in addition to headlining top jazz festivals. His stylistic blend was born in San Diego.

“What happened,” explained Porter, whose late mother was a minister, “is some gospel singer friends of mine from Bakersfield came down to one of Gilbert’s jam sessions with me. We did this thing one night at El Campo Ruse, downtown; it was gospel vocalizing, but jazzy at the same time, and the audience really loved it. People said: ‘We haven’t heard you sing like that before.’

“I don’t remember the song, but I still remember the melody. And it gave me the idea: ‘Let me bring in this gospel feel, which I already have in “Work Song” and (the Bobby Timmons-penned Art Blakey classic) “Moanin,” into my approach to jazz.’ It was an encouraging moment. We worked the song out on the corner on Market Street, then went inside El Campo Ruse and did it.

“It was an important moment for me. Because, in a way, there’s always a battle in jazz about what is ‘pure and true.’ Until then, I hadn’t embrace my understanding of gospel music in a jazz context. So it was like I had a little epiphany at that jam session with Gilbert.”

Castellanos fondly recalls the first time he heard the bearded Porter, who was already wearing the Kangol cap that has become the singer’s visual trademark.

“Gregory would pour his heart and soul into everything, and I was immediately impressed by his work ethic. He worked hard!” said Castellanos, now the curator of the San Diego Symphony’s Jazz @ The Jacobs concert series. Its first season concludes May 7 with Porter headlining. Castellanos will open the show in a trio with pianist Joshua White and bassist Marshall Hawkins.

“Another thing I really admired about Gregory,” Castellanos added, “was that he was very charismatic. He knew, even at the beginning stage of his career, how to connect with the audience.”

Lasting creative partnership

A gifted saxophonist, Kenyatta was also struck the first time he heard Porter, even in a classroom setting at UC San Diego.

“I knew, right off the bat, he had a special voice,” Kenyatta said. “He was just singing (wordless) horn parts, and I thought: ‘Oh, man, you need material crafted for you.’ We spent a lot of time listening to music, working on music, and talking about history, life and culture. Gregory has a very interesting mind beyond music.”

Kenyatta, who has produced or co-produced all four of Porter’s solo albums, proved instrumental to the budding singer’s career in many ways.

In the late 1990s, the visiting lecturer at UC San Diego had Porter accompany him to a Los Angeles recording session by jazz flute great Hubert Laws. Kenyatta was working as a producer and arranger on the 1999 album “Hubert Laws Remembers the Unforgettable Nat ‘King’ Cole.” Porter, by coincidence, cites Cole as one of his biggest early influences.

“Gregory watched Hubert and I work in the studio for hours,” Kenyatta recalled. “At the end of the day, I said: ‘Gregory, sing for Hubert.’ I put him on the spot. And he threw his head back, and sang, a cappella. As soon as he finished, Hubert said, ‘Let’s use him on this album!’ He asked Gregory to sing ‘Smile,’ and it’s on the album.”

It was around this same time that Porter hoped to land a role in the San Diego Repertory Theatre’s production of “It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues,” which went on to earn four Tony nominations on Broadway. He had previously appeared in the Rep’s 1998 production of the doo-wop revue “Avenue X.”

Alas, auditions for “It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues” had already been closed. But Laws’ sister, singer and “Blues” cast member Eloise Laws, was so impressed by Porter she arranged for him to audition. He did, and earned a leading role.

“I’m very thankful to San Diego for the musical opportunities it gave me,” said Porter, who — after nearly 15 years in New York — recently moved back to his hometown of Bakersfield with his wife and young son.

“Working at the Rep helped me get going in finding a way to use my voice. ‘It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues’ took me to Broadway, in the same production with the same people. ... Next thing I knew, I was in a Broadway show and living in Manhattan. ...

“So, in a big way, my concert in San Diego will be a homecoming. San Diego is where I really started to get my legs, musically.”

That Porter came here with dreams of football, not music, dancing through his head is a fact.

But Kenyatta, for one, has a hard time picturing Porter tearing up the gridiron, rather than captivating audiences at the 200-plus concerts the singer has averaged annually in recent years.

“I can’t even imagine Gregory as an athlete, even though he’s big and was a talented football player,” Kenyatta said. “He was on the same team at SDSU as Marshall Faulk. But I can’t imagine Gregory in that world, because he’s just too sensitive. I know he’s happier singing. They say that, when he was a child, if a bird fell out of its nest, he’d pick it up and try to nurse it back to health. He spent a lot of time walking, and thinking, by himself.

“Gregory may have become a singer, even without the injury, but he stands on his own. Very few musicians I know have achieved what he has. He’s always had a clear vision of what he wants to do, musically, and a unique style. It’s unique, but steeped in tradition. He’s like a branch of very strong tree. His songs are accessible, his voice is incredible and he’s a charismatic person, so it’s like a perfect musical storm.”

New artistic horizons

“Holding On”, the opening number on Porter’s new album, “Take Me to the Alley,” is his mesmerizing reinvention of the chart-topping 2015 hit by the English Electronic Dance Music duo Disclosure, which featured Porter on their original version. Porter’s version is slower and gracefully re-harmonized, with tasteful acoustic instrumentation replacing Disclosure’s bumping, electro-pop-meets-house version. What results could help introduce him in his own right to a new audience of open-minded EDM fans.

“It did occur to me when we were in the studio with Guy and Howard (Lawrence, the two brothers who comprise Disclosure) about maybe re-doing the song myself, then I forgot about it,” Porter said. “When I was putting ‘Take Me to the Alley’ together, I was like: ‘Let me see what my thoughts on the song are now.’ I liked the idea that it could be done, stripped down and spare, and still have the emotion about the irrepressible nature of love. For me, the message of the song is really important, maybe even more so than the instrumentation and the music.”

On “In Fashion,” Porter sings with impressive conviction that love should be enduring, not ephemeral, while deftly referencing (and then inverting) the piano motif from Elton John’s 1973 classic, “Bennie and the Jets.” Even better is the buoyant, brass-inflected "Don't Lose Your Steam" — a song Al Green might be happy to claim as his own — and “Take Me to the Alley's” gently uplifting title track.

A heartfelt ballad, "Alley" combines the sophistication of a Burt Bacharach classic with heartfelt lyrics about taking care of the sick and downtrodden, which Porter delivers with striking compassion. The result is a softly stirring song that is as inviting as it is inspirational.

“ ‘Take Me to the Alley’ is about trying to uplift the lives of people who have been afflicted, maybe the homeless or somebody with an illness, or maybe they’re refugees,” Porter said. “That’s not a popular thing that people want to hear in a song. I’m singing on this album about my son, my mother and relationships. If there’s something here that becomes a hit, cool, but it’s still an organic process for me. I’m not trying to get a (commercial) home run, and nobody at my record company has said: ‘You should go this way,’ or ‘You should be a dance artist.’ When I say ‘Take me to the alley,’ the ‘alley’ is generally the worst place, on one of the darkest streets in Bakersfield, where my mother would go and help people who needed help to redeem themselves.

“The message of any song is ultimately what slaps me in the head — and what slapped in the head when I was a kid. And, in jazz, the message is more pronounced than other things I’m listening to. I’ve always felt like getting your message across is more important than showing dexterity and doing melismas with your voice. I can do all that, and — at some points in music — it’s required, although in live performances more than on recordings.

“Sometimes, it’s a necessary device. And that’s not to diminish anything that happens in gospel music; in a way, you’re controlled by the spirit and don’t have any control of your voice. But I like the idea of sometimes simplifying what you’re doing to strike (people’s) hearts, emotionally. To me, if I contribute anything to jazz, it’s my vulnerability and really thinking about the emotion in each song.”

Whether “Take Me to the Alley” brings Porter fame here in his homeland remains to be seen. Either way, he has no doubt about his musical mission.

“The broader audience thing has happened for me in Europe, so I’m cool if that happens here,” he said.

“But I still know what my intentions are. And my intention is not for (achieving) fame; it’s to say something to people that moves them, emotionally. That’s the way it’s always been for me. That’s the way music affects me.”

george.varga@sduniontribune.com

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.