Making films through anthropologist’s eyes

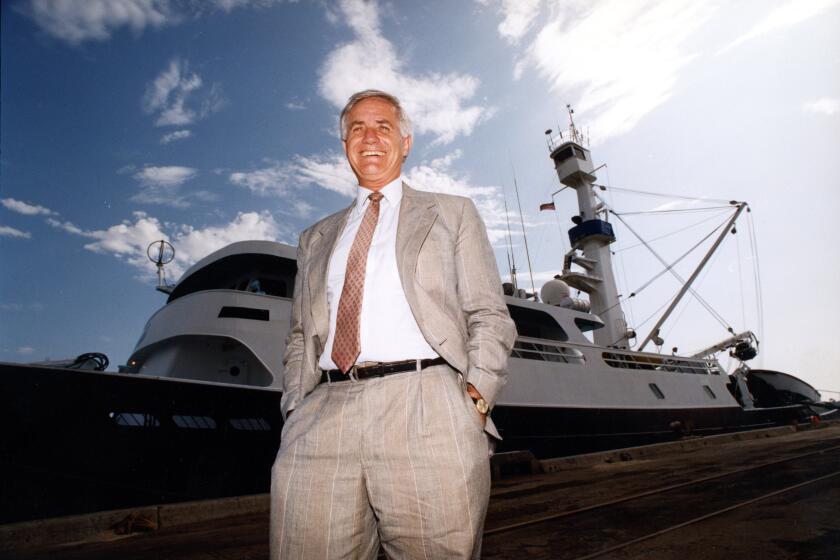

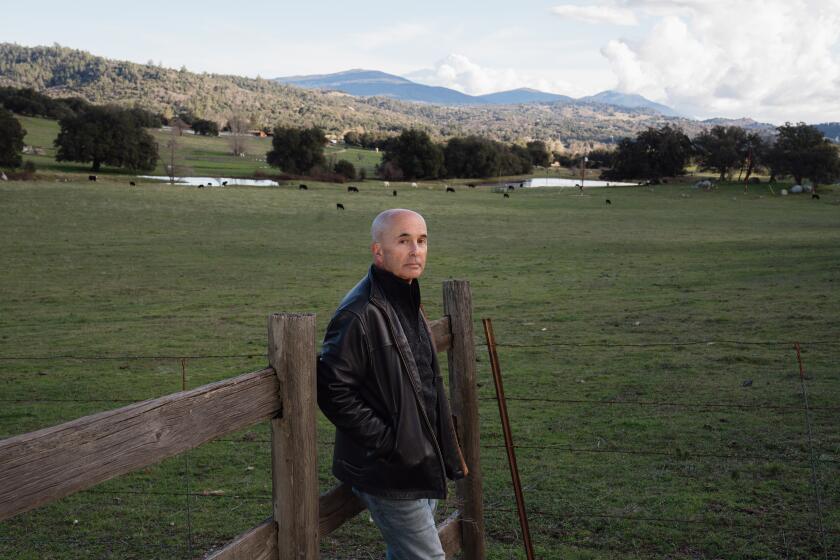

Paul Espinosa was an anthropologist before he was a filmmaker, which goes a long way toward explaining the kind of movies he makes.

For more than 20 years, working mostly in San Diego, he made documentaries focused on the U.S.-Mexico border, an area where cultures bump against each other, sometimes blending and sometimes clashing, an anthropologist’s dream.

The stories he told – about undocumented immigrants, about school segregation, about Pancho Villa, about farmworkers – won awards and helped shape how the rest of the nation understands this region and its history.

“He was a fortune teller of sorts,” said Hector Galan, a filmmaker in Austin, Texas who has collaborated with Espinosa. “The border issues that everybody’s talking about these days – he was on top of that early on.”

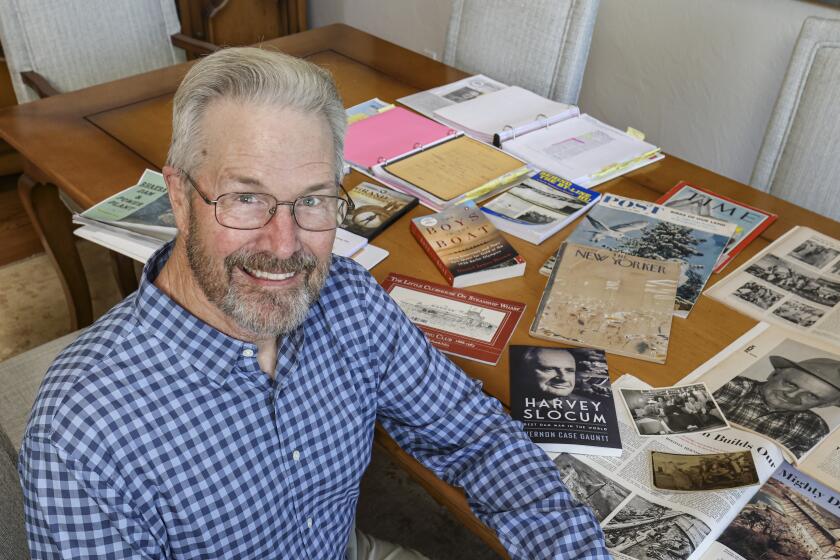

Now back in San Diego after a decade of teaching at Arizona State University, Espinosa recently donated his archives to UC San Diego. The 200 boxes of film scripts, correspondence, interviews (many of them with people no longer living), photos and other items will be used by scholars trying to assess the border, according to campus officials.

Saturday, the university celebrated the acquisition with a reception at the Geisel Library, where the Paul Espinosa Papers will be kept. The library is also sponsoring free screenings of three of Espinosa’s best-known films in the coming weeks.

It seems like a good time for the 65-year-old Espinosa to reflect on his career, except his career isn’t over, he said in an interview last week at his University Heights office. He’s in the editing stages with a new documentary, one about Ramon “Chunky” Sanchez, the veteran San Diego singer/songwriter and community activist.

Espinosa is also not one to spend much time thinking or worrying about his legacy.

“All I tried to do,” he said, “was open a window into a world that most people knew nothing about.”

‘Studying up’

Espinosa grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the son of educators who didn’t bring a television into the house until he was 14. It seems an odd beginning for someone who eventually made documentaries for the little screen.

But he thinks it helped that he wasn’t saturated as a child with TV images and stereotypes. By the time he went away to college at Brown University, the Ivy League school in Rhode Island, he’d grown curious about how the media works and how it shapes the world.

He majored in anthropology, then went to Stanford for graduate work. This was the 1970s, a time of anthropologists “studying up,” shifting from the traditional examination of powerless societies and focusing instead on institutions and cultures that wield significant clout.

Espinosa picked television as his study subject. He went to Hollywood, where he knew no one, and went around to the studios, asking for permission to observe them while they made their particular brand of sausage.

Rejected over and over, he finally persuaded Gene Reynolds (the writer, director and producer best known for MASH) to let him watch the inner workings of “Lou Grant,” a new show about a curmudgeonly newspaper editor. Espinosa would do his doctoral dissertation on the program.

Before that, though, he also did an internship at San Diego’s public broadcasting station, KPBS. The internship was designed to teach academics like him bout the media, the idea being that they would then go back to the Ivory Tower and be better able to translate the importance of their scholarly work to a general audience.

Espinosa never took up residence in academia, though. He liked it at KPBS, and folks at the station liked him, and he settled into a career there.

Right away, he saw a niche for himself – the border, seen through an anthropologist’s eyes. There weren’t many Latino filmmakers around, and he figured he could bring a different perspective to the work, tell different stories.

In 1983, he made his first big splash with “The Trail North,” a half-hour documentary about the Alvarez family and its journey through several generations from Mexico to the United States. Espinosa went to college with one of the family members, Robert Alvarez Jr., who appears in the documentary with his 10-year-old son, Luis, as they trace the ancestral migration.

Many TV depictions of Mexican-Americans at the time cast them as poorly educated and impoverished, if they were depicted at all. Robert Alvarez Jr. had a doctorate from Stanford and became a professor of ethnic studies at UC San Diego.

Luis? He grew up to be a professor at UCSD, too, in history.

National platform

When he worked at KPBS, Espinosa never viewed San Diego County as the only audience for his films. He thought they should be seen nationally, and they were, on the PBS network.

“The Lemon Grove Incident” (1986) was about what is believed to be the first successful legal challenge to school segregation, a case from the 1930s that predated the more famous Brown v. Board of Education by two decades.

“In the Shadow of the Law” (1988) was about four families living illegally in the U.S., one of the first in-depth films about undocumented immigrants and their everyday lives.

“Uneasy Neighbors” (1990) was about the tensions arising between upscale North County neighborhoods and nearby migrant worker camps.

And on and on, more than a dozen films. He won eight Emmys, five CINE Golden Eagles, a Golden Mike, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the California Chicano News Media Association. Four cities – San Diego, Phoenix, Albuquerque and El Paso – have held Paul Espinosa Film Festivals.

“A lot of the documentaries he did are still relevant today,” said Galan, the Texas filmmaker. “He recognized that the border is its own world with its own issues.”

In some ways, making documentaries is easier now than ever, Espinosa said. People are filming them on smartphones and editing them on laptops. “Anybody and his brother can become a documentary filmmaker,” he said. “It’s become something that’s considered chic.”

But it’s also harder, because money, especially from publicly funded arts organizations – the source of financing for many of his projects – is scarce.

Although some cultural observers worry about the future of documentaries in the age of YouTube and Instagram, Espinosa isn’t among them. He pointed to “Amy,” the film about singer Amy Winehouse, which was released in July and remained in theaters for months.

“There’s still a place for the long-form stuff,” he said. “Audiences want what they’ve always wanted. They want a good story.”

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.