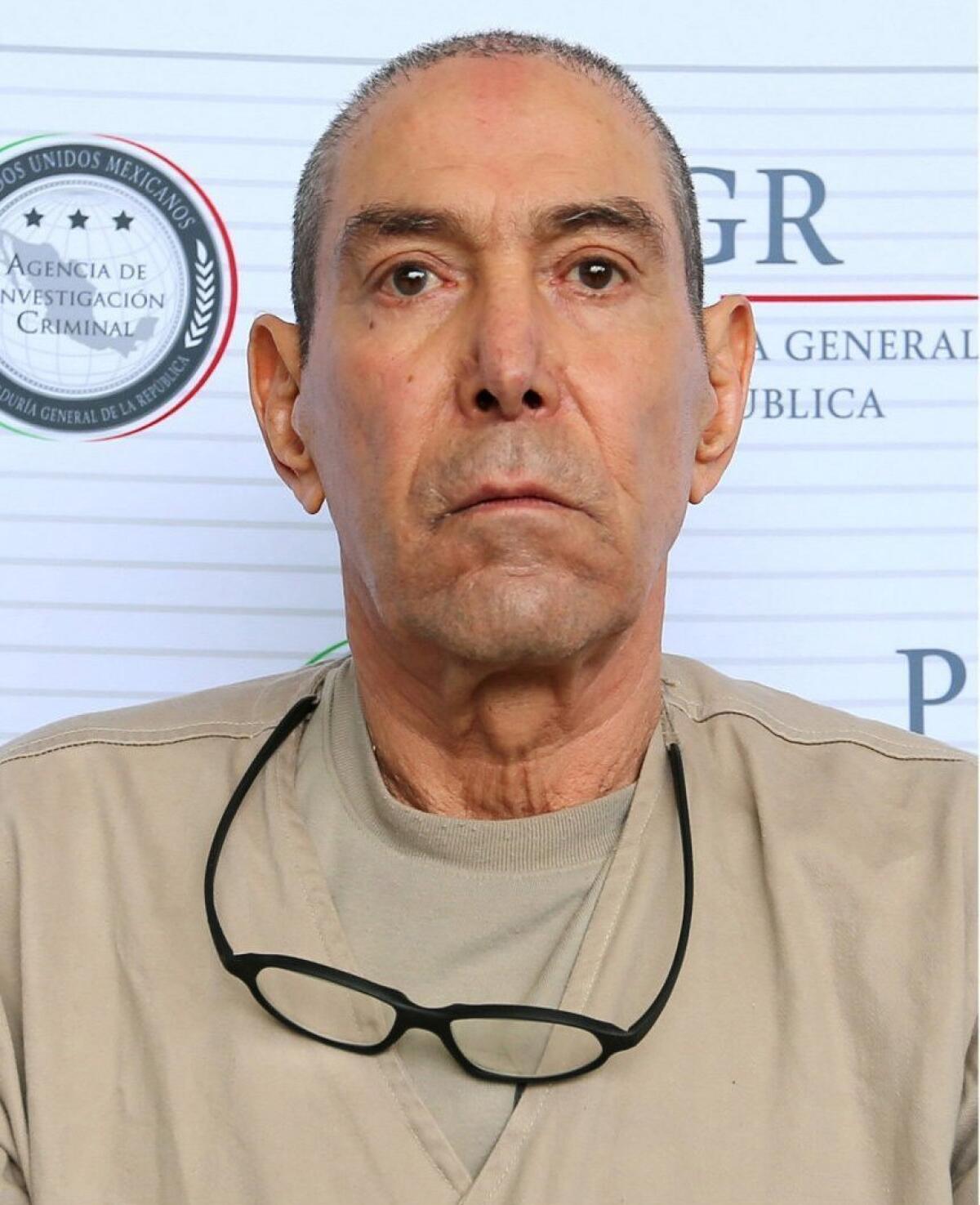

Drug figure extradited 20 years later

Antonio Reynoso Gonzalez was indicted in San Diego alongside one of Mexico’s most notorious drug lords two decades ago.

Yet for several years, he lived in plain sight just south of the border, enjoying a comfortable life in a mansion overlooking San Diego and prospering in elite business and social circles.

Until now.

Reynoso — also known as “El Ingeniero” or “The Engineer” — was among 13 top targets extradited to the United States this past week as part of a renewed cooperative effort with Mexico to cripple drug crime flowing between the countries.

There is speculation that the extraditions are an effort to patch international relations in the wake of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s brazen escape in a tunnel from a Mexican maximum-security prison in July. Since then, U.S. officials have made it clear that if and when the face of the powerful Sinaloa cartel is found, they want him to be shipped to the U.S. to face the many charges pending against him here.

“The Mexican government has basically been so humiliated by Guzman they’ve acknowledged they have to start extraditing (more) people,” said Nathan Jones, an assistant professor at Sam Houston State University in Texas who studies traffickers.

The U.S. Department of Justice referred to the extraditions as a “new era of collaboration” between the two nations.

“I am grateful to our Mexican counterparts not only for their assistance with this important matter, but also for their extraordinary efforts and unwavering partnership in our ongoing fight against international organized crime,” Attorney General Loretta Lynch said in a statement.

Many of the men extradited in the past week, including Reynoso, have ties to Guzman. Some were even incarcerated with him in the Altiplano prison from which the drug lord most recently escaped.

Details of the U.S.’s extradition request and Reynoso’s arrest were not released.

It has been a long and frustrating path for U.S. officials who have tried to broker Reynoso’s extradition over the past 20 years.

Reynoso and his two brothers, members of a well-to-do family grocer business, were named in a 1995 indictment against 23 people — including Guzman — suspected of transporting cocaine from Mexico to Los Angeles.

In 1993, Mexican authorities in Tecate discovered seven tons of cocaine in a semi-truck shipment of La Comadre chili peppers, a food company owned by the Reynosos.

A month later, Catholic Cardinal Juan Jesus Posadas Ocampo was gunned down mistakenly in a shootout between Guzman’s men and members of Tijuana’s Arellano-Felix cartel at the Guadalajara airport.

The violence led to Guzman’s arrest. (He later escaped from a prison and was on the run for 13 years before his 2014 capture.)

A map found in one of his safe houses also led to the discovery of a 1,416-foot-long tunnel nearly complete under Otay Mesa. The 65-foot-deep tunnel, referred to then as the “Taj Mahal of tunnels” for its sophistication, ended just short of a cannery and warehouse being built for another Reynoso family food business, Tia Anita.

But the tunnel plans were a bit off. Authorities believe the tunnelers were relying on an inaccurate San Diego County map that showed 1,416 feet to be the exact length between the start of the tunnel and the cannery.

The indictment also relied on recorded phone conversations, including one that implicates Reynoso in the 390-kilo shipment of cocaine to Chicago.

One of Reynoso’s brothers, Jose Reynoso, pleaded guilty in 1996 in San Diego federal court to conspiring to smuggle cocaine in soap cartons and cans bearing the La Comadre label. He also admitted the tunnel was to be a drug-smuggling corridor. He was sentenced to 12½ years.

Yet Antonio Reynoso eluded U.S. authorities. He is not wanted for any crimes in Mexico.

A 1997 Los Angeles Times article described the frustration of U.S. authorities who watched helplessly as Reynoso constructed an elaborate compound — complete with turret, glass pool atrium and green roof — that backs up to the U.S. border. It is a landmark Border Patrol agents frequently pointed out to visitors, the story noted.

A year earlier U.S. officials had asked their counterparts in Mexico City to issue an arrest warrant for him, saying that they would initiate the official extradition paperwork once he was in custody, the Times reported.

In 1999, Reynoso’s name was invoked during a U.S. congressional address that blasted the nation’s growing drug crime problem. He was listed among a dozen suspected drug traffickers on the U.S.’s Mexico extradition wish list.

Jones, the professor, said it’s not unusual for Mexico to show reluctance to extradite someone like Reynoso.

“With a combination of wealth and high-level connections, it could be fairly common,” he said.

There is also the fear of how much intelligence a valuable target may share with U.S. authorities, and how much the U.S. might pass on to Mexico, Jones said. Some of that intelligence could also implicate corrupt officials.

Authorities have not disclosed when Reynoso will make his first appearance in San Diego federal court.