Descendants thankful for Mayflower ties

For most of us, the Pilgrims are figures of legend and lore, vaguely remembered from elementary school lessons as those people who arrived from England on the Mayflower almost 400 years ago and had something to do with Thanksgiving.

To hundreds of San Diego County residents, though, ties to the Pilgrims run deeper. They’re family.

“It makes Thanksgiving more than just a fancy turkey dinner,” said Ray Raser, an officer with the San Diego Colony of the Society of Mayflower Descendants. “It becomes a history that you feel a part of.”

Genealogists believe there may be 30 million people worldwide descended from the Mayflower passengers, but only 29,000 are society members. That’s because to join, you have to prove your lineage. It’s not enough for claims of Pilgrim blood to be passed along in table talk by Aunt Maude or Uncle Harry. There have to be records: birth certificates, marriage licenses, wills, land deeds.

It’s easier than it used to be, thanks to various Internet search services, but it still takes time and persistence to trace back through a dozen or more ancestors — to get past parents and grandparents and great-grandparents, past both world wars, past the Civil War, past even the Revolutionary War.

Often that means visits to church basements and cemeteries, to county clerks’ offices and courthouses. Every Mayflower searcher has stories of disappointing dead-ends and exhilarating Eurekas.

Those who have been able to connect the dots to Plymouth Rock come from a variety of livelihoods and backgrounds. “It’s not just a club of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants anymore,” said Walter Powell, executive director of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, the national organization founded in 1897 that oversees all the local colonies.

The ranks through the years have included the famous (Julia Child, Clint Eastwood, Marilyn Monroe, Hugh Hefner) and the powerful (Presidents Adams, Bush, Grant, Roosevelt). These days, members typically are in their 60s or older, the age at which many begin to have the inclination (and the time) to research their roots.

With more than 300 members, San Diego County is home to one of the largest and most active Mayflower groups in California, which in turn has the second largest state society in the country. The largest is in Massachusetts, where the Pilgrims landed and where the national organization is headquartered.

This is a particularly busy (and proud) time of the year for members because of Thanksgiving. Saturday, they gathered at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar for an annual meeting celebrating the anniversary of the Mayflower Compact, the document that framed how the fledgling settlement (and eventually the United States) would be governed.

Some of the members dressed in period costumes. They stood when the the names of their Mayflower kin were read out loud. They passed around five kernels of corn, a reminder of the daily rations the Pilgrims received during what’s remembered as “The Starving Time.”

Saints and Strangers

When the roughly 100-foot-long Mayflower anchored near the northern tip of Cape Cod in November of 1620, its 102 passengers had been sailing for about two months. They were sick and tired and they were in the wrong place, well north of the Virginia Company they had hoped to join.

Most had come to America as Separatists to escape religious persecution in England and Holland, but some had other reasons, chiefly financial, for starting over. Saints and Strangers, these two groups of people came to be known.

Almost 50 people died that first winter, victims of disease, malnutrition and the elements, and by the next fall, the survivors felt a need to count their blessings. They shared a three-day festival of food with the Wampanoag Indians who had helped them gain a foothold there. It was the first Thanksgiving in Plymouth, although nobody called it that then, and over time it’s been mythologized as the first Thanksgiving ever, which it wasn’t. Both the Native Americans and the English had traditions of celebrating successful harvests.

It took about 240 years — Abraham Lincoln was president and the Civil War was raging — for Thanksgiving to become a national holiday, and now it’s embedded in our cultural identity and on our calendar.

On the fourth Thursday of every November, families gather for food and fellowship, and in countless households, a familiar boast is made: We had relatives who were on the Mayflower.

Joyce Shiloff heard her father say that many times when she was growing up. She always rolled her eyes, because he never had any proof.

“I didn’t believe it for a second,” the University City resident said. “It just didn’t seem possible given our family background.” As far as she knew, the ancestors on her mother’s side came from Italy, her father’s from Ireland.

But then she took a trip with her father and her sister to Massachusetts in the 1990s, to visit places he knew growing up, and they came across family names in museums and genealogy books. She started to think maybe her father’s claim was true.

After he died, she dug some more and found the link: her grandfather was married to a woman whose lineage stretched back to the Pilgrims. “I’ve always regretted that my dad never found out for sure that we were Mayflower people,” Shiloff said.

Eventually, she unearthed ties to several other Mayflower passengers, including William Brewster, the religious leader of the Plymouth Colony.

That’s not uncommon, to have multiple connections. Several of the passengers got married after they came to America. Some of those getting married were the sons or daughters of other passengers, and then their kids married the kids of other passengers, and so on.

Among the descendants, some Mayflower passengers are more interesting than others, and more coveted. There’s frequent pride in being related to Brewster or to Miles Standish, the colony’s military leader.

And some get a kick out of being kin to John Billington, the black sheep of the Pilgrim family.

Billington feuded with other settlers. He insulted Standish. He was implicated in a failed revolt. Then he shot and killed a neighbor, was convicted of murder, and hanged.

Shiloff has been trying to find links to another prized Mayflower ancestor, Stephen Hopkins, who is believed to have been at Jamestown before he was at Plymouth — a New World two-fer.

“I would love,” Shiloff said, “to have my Hopkins.”

Going home

Many of the Mayflower descendants have Pilgrim-related house decorations that stay up year-round, not just at Thanksgiving. They have replicas of the ship, portraits of their ancestors, certificates documenting their ties.

But this is still a special time of the year for them, and some make a point during their family feasts to acknowledge the early days of the tradition they are enjoying. “All these years we’ve been celebrating Thanksgiving in this country and in our family, and to learn we have a personal connection to it — that’s still amazing to me,” said Budd Leef, who lives in Rancho Peñasquitos.

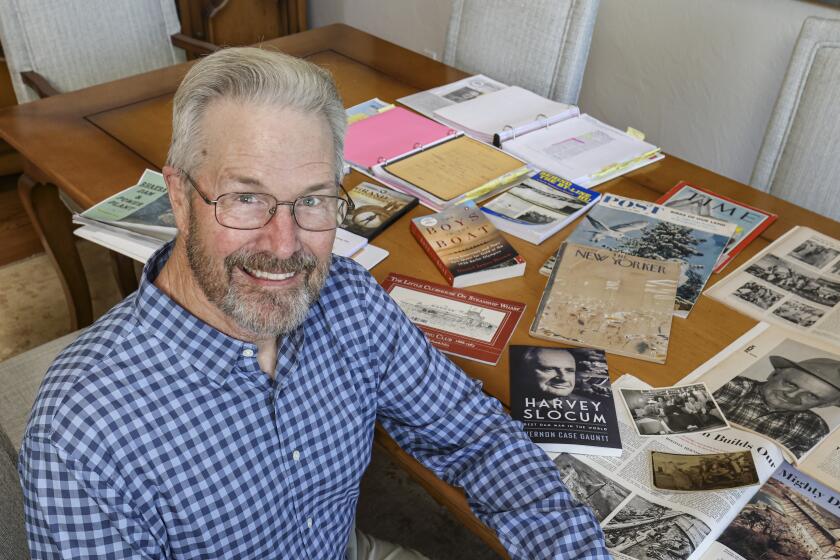

He came to his Mayflower roots in a roundabout way. He spent a couple of decades doing the genealogy on his father’s side, looking for (and eventually finding) relatives in Sweden. When he was finished, his mother said, “Do mine now.”

Leef wasn’t thrilled about another long slog through official records, but the family already had paperwork going back five generations. He went on the Internet and in less than two days found a Pilgrim connection. “I was so excited I woke my wife up at 1 in the morning to tell her,” he said.

That was five years ago, and like a lot of the descendants, his discovery launched a journey into all things Mayflower. Books. Movies. And of course membership in the local colony. Leef is now the group’s historian.

Some get so fascinated with it all that they take trips to Plymouth or go to England and Holland to see where the Pilgrims started. “It gives you an appreciation for the price they paid and the harrowing journey across the ocean,” said Raser, the colony’s corresponding secretary and former governor. His wife, Gail, is the current governor. They live in San Pascual Valley.

He remembers walking the places where Brewster was born and lived and visiting the cell where he was imprisoned for his religious beliefs. “It was a very unique feeling,” Raser said. “I felt like I belonged on that ground.”

It felt, he said, like home.