Nobelist to keep Salk focused on basic science

Bench to bedside.

These days, you hear the phrase virtually everywhere in San Diego’s huge science community. With growing intensity, researchers are trying to turn lab discoveries into new drugs and therapies.

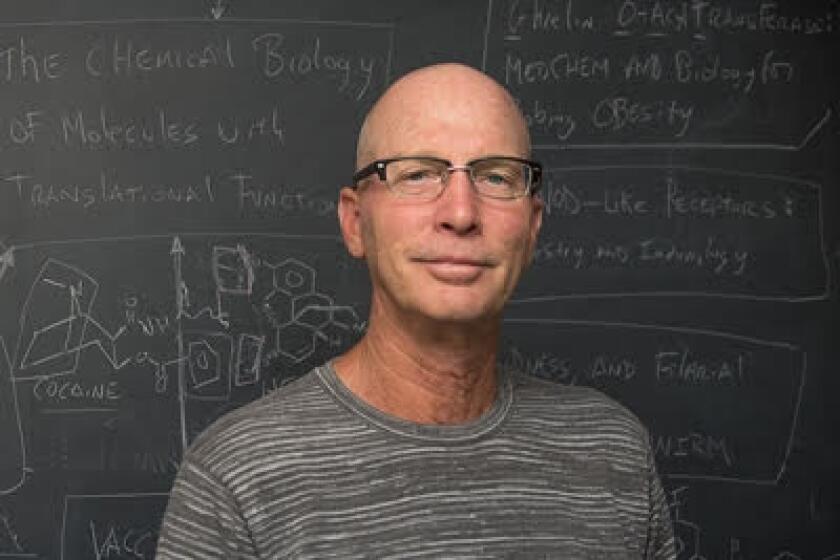

The big exception is the elite Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, which reaffirmed its commitment to basic science last week by naming Nobel laureate Elizabeth Blackburn to be its next president.

Her mantra has long been: “I want to understand how living things work.”

Blackburn, a biochemist, spent decades studying telomeres, the tiny caps at the end of DNA strands that protect chromosomes. Her foundational work led to major insights about human biology, earning her a share of the 2009 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

Her focus isn’t expected to change when she succeeds Dr. William Brody as Salk’s president on Jan. 1.

“Basic science is the bedrock of the Salk,” said Blackburn, whose parents were family physicians. “It feeds translational medicine. They’re not in opposition. This is a continuum.”

The Salk is flanked by UC San Diego and other institutions deeply involved in basic science. But these same places are also rapidly expanding their efforts to translate new discoveries into medications, other treatments and equipment.

Since 2013, private donors and foundations have given local scientists more than $525 million in gifts and grants to speed up efforts to find treatments against cancer, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and other diseases.

Reflecting a national trend, San Diego philanthropists such as Denny Sanford and Ernest Rady have effectively said: Basic science is essential, but it’s not enough.

That perspective hasn’t left the Salk Institute out of the loop.

Over the summer, the nonprofit institute reached its goal of raising $300 million in private donations. The figure has since climbed to $340 million.

Brody publicly launched the campaign in 2012 to shore up the Salk’s finances and make the institute less reliant on the National Institutes of Health, the largest source of public funding for biomedical research.

The private donations support the original vision of institute founder Jonas Salk, who developed the world’s first effective vaccine against polio. He believed that its scientists should be free to pursue any idea they wanted, rather than just choosing ones that might lead to new drugs.

The Salk evolved into a famed institution that found itself in need of fresh leadership this past summer when Brody announced that he would retire. His departure comes at a sensitive time. Although Brody proved to have the Midas touch in fundraising, the institute still needs to raise a lot more money.

Last year, NIH funding for the Salk dropped by nearly $7 million from the previous year. And the institute faces the cost of replenishing faculty and investing in technology so that it can continue to progress.

A search committee quickly turned to a familiar figure — Blackburn. She has spent most of her career at UC San Francisco. But since 2001, she also has been a non-resident fellow at the Salk, which has periodically brought her to the La Jolla campus.

The committee and Salk’s faculty at large viewed her as an extraordinarily gifted researcher whose warm, engaging personality also made her well-suited to talking with donors and the general public.

As it turned out, Blackburn was looking for a fresh challenge when the offer came.

“I’ve been ramping down my research for awhile now,” said Blackburn, who will turn 67 on Thanksgiving Day. “The kind of things you do as a Nobel laureate take up a lot of time. And I came to realize that I want to do more to promote science, and that I wanted to participate at a place like Salk.”

Blackburn, who speaks in a soft, lilting voice, added: “I don’t want to be corny and say that the Salk is magical. But Jonas Salk’s vaccine benefited people who lived in terror of polio. Then he had a vision for an institute that would do great science, which it does. The Salk is the jewel of science.”

For personal and practical reasons, Blackburn’s decision to accept the institute’s presidency has sent a jolt through the campus, which is known for its serenity.

“It’s hard to get someone of her level to take on this kind of leadership position,” said Ronald Evans, a Salk biologist who has known Blackburn since 1977. “It really makes a statement about us. We’re an elite institution, but science is a marketplace. And this will help us compete for faculty.”

Salk biologist Roger Guillemin, who won a Nobel Prize in 1977, said Blackburn also will help the institute appeal to potential donors.

“There’s no doubt that having a Nobel laureate speak in the name of the Salk Institute on whatever subject will add weight to whatever is being discussed,” Guillemn said. “Particularly, I would say, when dealing with possible donors not particularly knowledgeable in the implications of what is being discussed or proposed.”

Salk neuroscientist Terry Sejnowski said it’s valuable to have a top-notch scientist leading the institute.

“Science is changing rapidly and the Salk has to decide where to use its limited resources to hire new faculty and where and when to move into new areas. These are multimillion-dollar decisions,” he said. “We are very well-positioned to move ahead.”