Life after move for Chargers fans?

Experience in other cities, academic studies offer insight

It will hurt, Chargers fans. Hurt a lot. Hurt like losing a close friend.

But there is life after the jilting. You can still follow football. Or find something else to get passionate about, to feel a connection.

Think what else you can do with that extra eight hours a week (the amount an average fan in the U.S. spends following sports through various media).

That’s the word from people in cities where pro football teams have left. Theirs is the anguished voice of experience, worth listening to as the Chargers get ready to play what may be their final season in San Diego.

Related: San Diego takes aim at Chargers' Carson plan

“Looking back, I think I took it for granted the Rams would always be here,” said Tom Bateman, who grew up in Anaheim cheering for the team before it moved to St. Louis in 1995. “When they weren’t here, it was very surreal.”

Bateman said he was angry, and a little lost. He didn’t cheer for the Rams in their new city. He didn’t go looking for another team to fill the void. “I enjoyed the sport and the NFL, but I had no personal investment any more,” he said.

Peter Weinberger was turned into a football wanderer, too. Born and raised in Cleveland, he grew up a Browns fan. When that team moved and became the Baltimore Ravens in 1996, “the whole thing was like something from outer space,” he said. “I could not believe the Cleveland Browns did not exist any more. They’d been here almost 50 years.”

He was living in San Diego at the time, running a restaurant. He still watched football but “I didn’t have the same feeling about it,” he said. “It made no difference to me who won or lost.”

For him, there was a happy ending. In 1999, the Browns were resurrected as an expansion team. Since then, the team has often been disappointing – it’s never been to a Super Bowl – but that’s not what matters, according to Weinberger, who moved back to Cleveland three years ago.

“It’s just ingrown here, following the Browns,” he said. “People become fans as children through their parents, and it just gets passed on down the line. It’s a religion here.”

It’s too soon to know whether the Chargers will be heading north to Los Angeles, too soon to know how the faithful in San Diego will react if they do.

Some, though, are already in the early stages of grieving.

Why fans care

Daniel Wann is a psychology professor at Murray State University in Kentucky, where he specializes in studying sports fans.

One of the things his research has consistently shown, he said, is that fans who align themselves with the local team often have a higher level of social well-being. They have better self-esteem, lower levels of loneliness, a stronger connection to others in their community.

“We’ve known for a long time in psychology that being linked up with others is a good thing,” he said.

There’s a dark side to extreme fandom, people who get so wrapped up that their personal relationships and work performance can suffer, or they lash out violently when the outcome of a game isn’t what they’d hoped. But those are rare, Wann said.

For many fans, a favorite team also becomes part of who they are, according to Eric Simons, a Bay Area science writer and author of “The Secret Lives of Sports Fans: The Science of Sports Obsession.”

“Where can you find some stable place to anchor your identity, your sense of self?” he said. “One way is to say ‘I’m a Padres fan’ or ‘I’m a Chargers fan’ and for many people that’s more stable than an identity linked to a marriage or a job. If you find it with a team, no one can take that away from you. Unless, of course... “

Unless, of course, the team moves.

Simons said the depth of “trauma” over a move depends on what kind of connection fans feel to the team. In his book, he compares what happened in Cleveland when the Browns moved to what happened when the Raiders moved (first from Oakland to Los Angeles, then back).

In Cleveland, the connection fans felt was to the team and its rich history, which is why when Art Modell took the franchise to Baltimore, he had to leave behind the Browns name and uniform colors, in case Cleveland got another team. Which it did, and it’s called the Browns, and the players wear burnt orange and seal brown.

“For crumbling Rust Belt cities with a lot of things going wrong,” Simons said, “sports teams can be important anchors.”

Contrast that with Oakland, where the strongest connection fans feel is with each other – to Raider Nation. “They look at themselves as family,” Simons said. “If the team moves, who cares? Raider Nation doesn’t change. The meaning they get from the team is not geographically grounded.”

Letting go

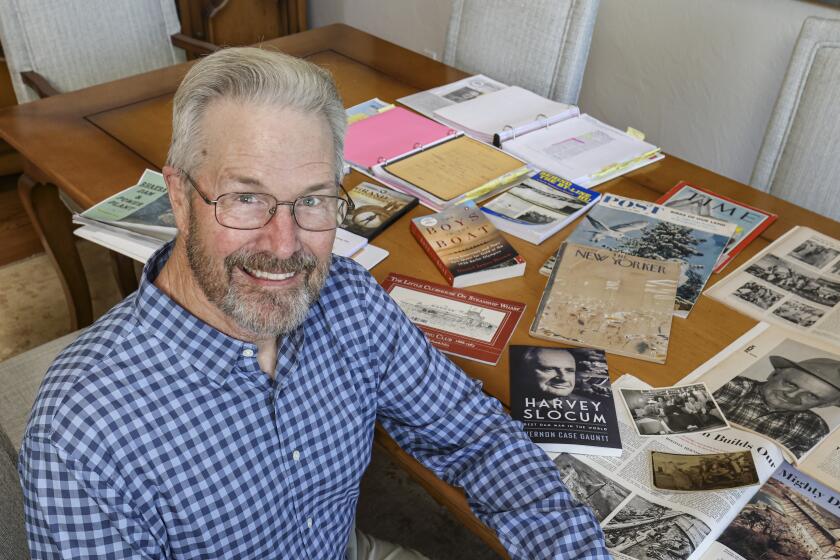

Where San Diego fans fit into all this is evolving. Tommie Vaughn, who runs a Chargers website

(chargertom.com) from his Escondido home, said he will watch the team on television if it moves to L.A., but he won’t spend any money on tickets or merchandise.

“I’ll shut the website down the day they leave,” he said. “It will kill me, and it will be a sad day in my life. But it’s a sad event.”

Being a Chargers fan since the early 1960s has meant “everything” to him, he said. “It’s the sense of being a part of something.” He said he couldn’t begin to calculate how many hours each week he spends writing, reading, talking and thinking about the team.

One of the most thrilling days of his life was being at the stadium in 1995 with thousands of other fans the night the Chargers returned after beating the Steelers in Pittsburgh and qualifying for the Super Bowl.

“There’s nothing that will compare with that feeling,” he said.

He has pictures of his family, five generations of relatives, everybody in Chargers’ gear. They’re scattered now around the state and the country, but they always call or text during games. When he travels, he wears a Chargers hat, and invariably somebody sees it and nods or says something. “It’s a community thing, community pride,” Vaughn said.

Tom Whiting has six season tickets to the Chargers, a team he’s been following since they played in Balboa Stadium. It costs about $7,400 for the tickets, plus another $500 for parking.

The family usually travels from Mission Beach to Qualcomm about four hours before game time for tailgating. They know the people who gather in the nearby spaces, have watched kids and then grandkids join the festivities.

Whiting and his wife follow the team a couple of times each year for away games, too. Last season, in Kansas City, it never got warmer than 20 degrees.

All that money, all that time and effort - what happens if the team relocates to Los Angeles? “We’re done,” he said. “You might as well stick a knife in my heart.”

He said he’d probably watch the team on TV, and maybe travel to an away game if the city and time of year was right. But buy tickets to a home game somewhere other than San Diego?

“It’s been great fun, but no,” he said.

Not that he didn’t think about it. Coming down through L.A. recently, he started the odometer in Carson (proposed site of the new shared Chargers-Raiders stadium) and stopped it at his house: 110 miles.

“I can’t imagine doing that,” he said.

The trip, on a Wednesday afternoon, took three hours.

An opportunity?

Not everybody thinks it will be a bad thing for Chargers fans if the team leaves town. Some see it as an opportunity for change.

Steve Almond is a Massachusetts-based author of “Against Football: One Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto,” a scathing 208-page farewell to a sport he’s loved for 40 years.

“Football,” he writes, “is rotten on all sorts of levels.”

He cites the mounting evidence of brain injuries to the players. The financial manipulation of cities. Racism. Gender stereotypes. Greed.

“I’ve always thought football was the most suspenseful, exciting athletic endeavor you could watch,” Almond said. “But when I looked at everything that is going on, I decided I had to step away and stop being a sponsor of this. Because that’s what fans are – the sponsors. We’re the reason the owners have so much leverage.”

Almond was a Raiders fan when the team moved (twice) and offered some advice to Chargers’ fans. “Recognize that it does not matter how angry you are, how disappointed and disgusted you are. The only thing that matters is whether you buy their gear, watch their product. The bottom line. And the only way to affect the bottom line is by not buying.”

Some Chargers fans might follow Almond out the door. Some might ignore him. If the team leaves San Diego, everybody will have to make up their own minds about how to react.

“They may feel almost embarrassed about caring so much about a football team,” said Wann, the Murray State professor. “But for the die-hard fan, it’s not just a team. It’s part of who you are.

“The first thing they should do is not feel bad about feeling bad.”