Cure for AIDS may be not that far off

Once mostly fatal, now manageable disaease, could be conquered in the foreseeable future

(Please see accompanying article on fighting the stigma of having HIV.)

AIDS was once considered a virtual death sentence. Scientific advances have turned it into a manageable disease. Now there’s reason to hope that final victory — a vaccine preventing infection, and an actual cure — may be possible in the foreseeable future.

The struggle against AIDS and HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, has taken place for 35 years. The gloom of the early days began to dissipate in the mid-1990s when effective anti-HIV drugs were discovered.

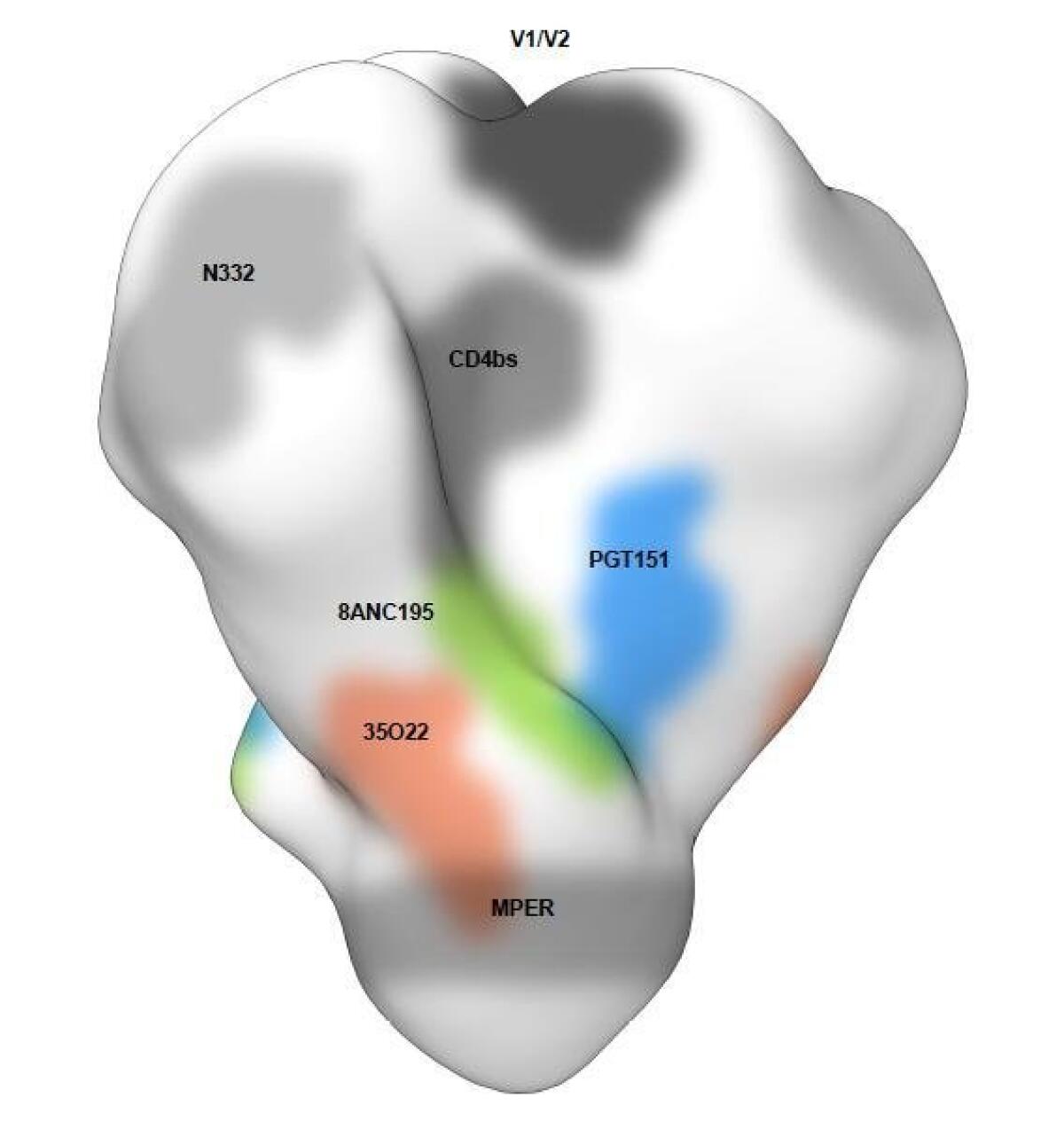

And the discoveries keep coming. Vaccine researchers keep finding weak spots in HIV vulnerable to powerful “broadly neutralizing” antibodies. Last week, another weak spot, the seventh discovered so far and the third this year alone, was reported. All three have been identified by teams including scientists from The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, a major center of vaccine research.

View the Video Designing an HIV Vaccine

AIDS researchers who have worked in the field from the beginning, such as Dr. Anthony Fauci, marvel at the change in patient survival that anti-HIV drugs have accomplished.

“In the early ’80s, the median survival time of my patients was six to eight months,” said Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “Today, if a 25-year-old comes into the same clinic that I took care of them 30 years ago ... you can project they will live another 50 — that is five-zero — years.”

This staggering transformation of one of the most relentless diseases into something that can be lived with bears evidence that the expenditure of billions of dollars and untold hours of research and treatment are paying off.

HIV has been attacked from nearly every conceivable angle, from drug therapy to discouraging risky behavior. Public health programs such as providing condoms and promoting education about avoiding high-risk behaviors complement the medical and scientific advances in understanding and blocking HIV.

And under a program called PEPFAR, created in 2003 by President George W. Bush, lifesaving HIV drugs have been sent abroad to impoverished populations who can’t afford them.

The result of this kitchen-sink approach, Fauci said, is that over the past 10 years, the number of deaths from HIV worldwide has dropped 35 percent, as has the number of new infections.

And while no effective vaccine is available, creative use of drugs to block AIDS infection provides the next best thing. Using what is called “pre-exposure prophylaxis,” medication is given to those at high risk, such as non-monogamous gay men and intravenous drug users, who can pass along fluids containing HIV.

“If you give them one pill a day of a drug called Truvada, you can dramatically diminish the likelihood that they will be infected,” Fauci said.

Treating infected people to bring their viral levels below the limits of detection also greatly lessens the chance they will pass along HIV to an uninfected partner.

Treatment breakthroughs

A drug called Retrovir, or AZT, provided the first real breakthrough for treating AIDS. The drug, approved in 1987, inhibits replication of the virus. That gives the patients’ immune system a break from the continual viral assault.

AZT is far from ideal, causing side effects including acid reflux, anemia and liver damage. So drug companies searched for better drugs. The goal, then and now, is to reduce the “viral load” to such a low level that mutations are also inhibited. Fewer virus particles means fewer chances to mutate and develop resistance.

Protease inhibitors provided another breakthrough. These drugs target a viral enzyme HIV needs to replicate.

One of the first protease inhibitors was Viracept. Developed by San Diego’s Agouron Pharmaceuticals, Viracept was approved in 1997.

Agouron’s success marked it as a biotech company to watch. One of those watchers, drug giant Warner-Lambert, purchased Agouron in 1999. The following year, Warner-Lambert itself was purchased by Pfizer. The former Agouron headquarters is the site of Pfizer’s La Jolla operation.

As the number of approved HIV drugs accumulated, doctors came up with the strategy of giving multiple drugs at once. This “cocktail” strategy hammers the virus from several directions, boxing it in so it has less of a chance to develop resistance.

Toward a possible cure

The HIV vaccine program is expected to start clinical trials in about two years. It’s been helped by a better understanding about how potent “broadly neutralizing” antibodies keep HIV in check.

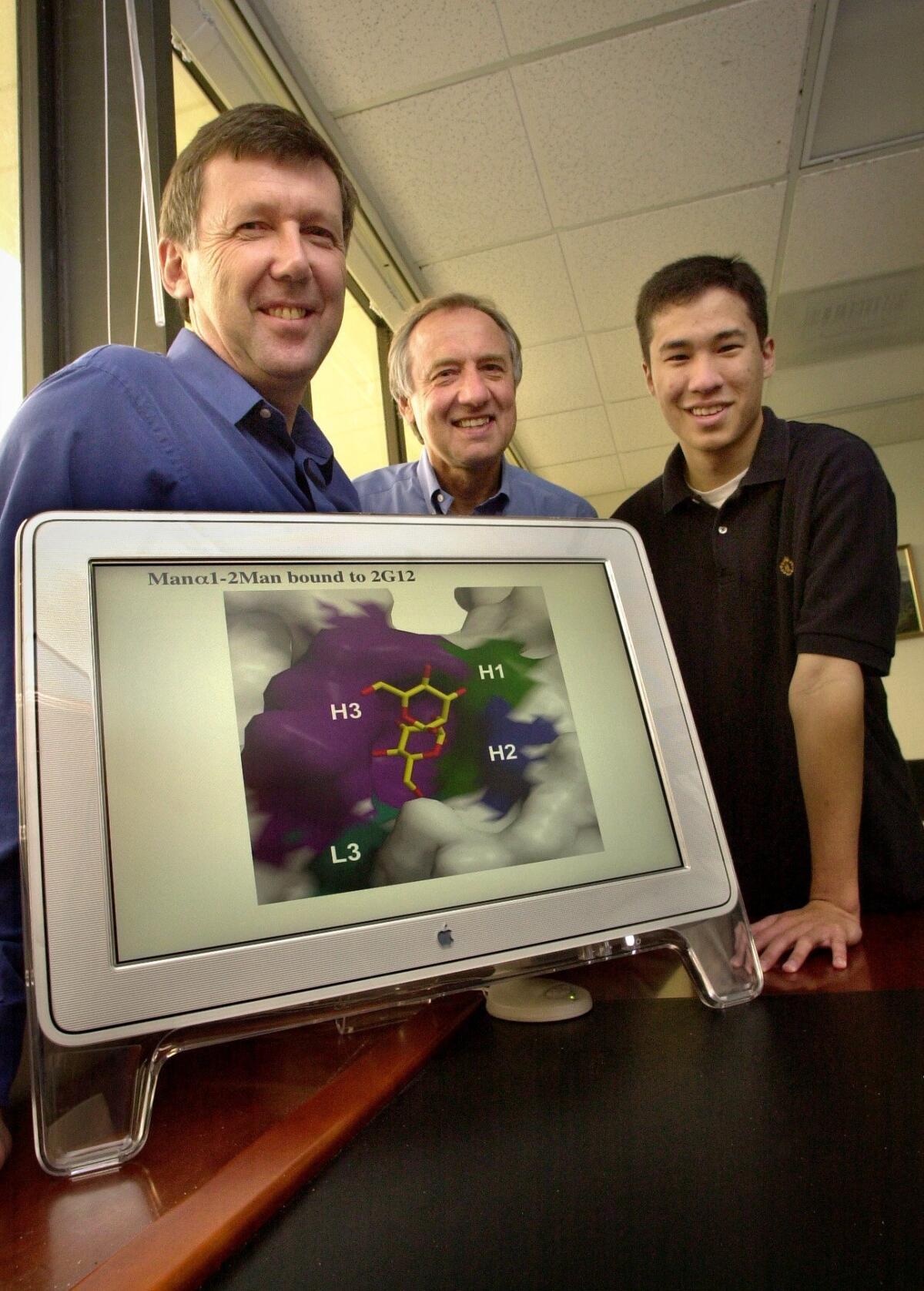

Much of this knowledge comes from work at Scripps Research, which in 2012 was awarded $77 million from the National Institutes of Health to run a center called Scripps Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology and Immunogen Discovery, or CHAVI-ID.

The center is collecting these antibodies and studying them to use as templates for vaccine design. It’s led by Dennis Burton, and includes Scripps Research colleagues Ian Wilson, Andrew B. Ward, along with other major HIV researchers from across the country.

Broadly neutralizing antibodies stop a wide range of HIV strains. They target areas of the changeable virus that must remain constant for it to infect cells. They were discovered in HIV patients that had remained healthy, resisting the progression to AIDS.

These antibodies physically block the virus from entering cells. The exact location of attachment is important to know because neutralizing antibodies that attach to the same site don’t constrain mutation as effectively as targeting different sites at once.

In 2013, Scripps Research scientists reported finding that a previously identified vulnerable site was much more extensive and easily accessible than first believed. They dubbed this promising target a “supersite,” in a study published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

When newly examined broadly neutralizing antibodies are found to bind to a different site than the others, this means a new vulnerable site has been discovered. That’s what was reported last week, coming after similar reports in April and May.

In 2013, Scripps Research scientists reported finding that a previously identified vulnerable site was much more extensive and easily accessible than first believed. They dubbed this promising target a “supersite,” in a study published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

When newly examined broadly neutralizing antibodies are found to bind to a different site than the others, this means a new vulnerable site has been discovered. That’s what was reported last week, coming after similar reports in April and May.

In Los Angeles, a company called Calimmune is now testing the Holy Grail of AIDS therapy — a cure.

Calimmune removes and genetically engineers the immune cells of patients, the very cells HIV infects and destroys, then reinfuses them. The experiment attempts to replicate the experience of Timothy Brown, an HIV-positive man who received a stem cell transplant after being diagnosed with a blood cancer.

The transplanted cells contained a mutation that blocks HIV.

Today, Brown is free both of cancer and symptoms of HIV infection. While the virus is still in his body, the engineered immune cells repel infection.

By some accounts, Brown can be considered to be cured of HIV, the first person with that distinction.

The benefits of fighting HIV extend to other dangerous viral diseases.

“It has really matured the field of targeted antiviral development,” Fauci said. “It has brought that art form to a new level, where you take the components of a virus, crystallize it, determine what the component is vulnerable to, and make a molecule to block and bind it.

Efforts to stop Ebola, such as the drug ZMapp, follow that strategy. San Diego-based Mapp Biopharmaceutical is developing the drug with the assistance of Scripps Research scientists. Equipment purchased for Scripps Research’s vaccine effort is being used to study Ebola antibodies.

However, many previous declarations of progress in HIV vaccines have been dashed by bad results. None have proved effective enough to approve. The Immune Response Corp. of Carlsbad, cofounded by the late polio vaccine developer Jonas Salk, went under after spending millions of dollars and many years in failed efforts to develop such a vaccine.

“I think the honest answer about how far along we are is that we don’t know,” said Burton, the Scripps Research researcher. “It depends on whether certain discoveries are made. It’s very difficult to predict.”

Milestones in AIDS research and treatment

1981: AIDS first identified; but cause unknown.

1984: The human retrovirus HIV identified as the cause of AIDS.

1987: Food and Drug Administration approves AZT, the first drug to treat AIDS.

1995: FDA approves first protease inhibitor, Invirase, leading to treatments making AIDS a manageable disease.

2014: Researchers find three more vulnerable sites on the virus, raising hopes for a vaccine to prevent HIV infection.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.