The Navy’s ‘Corvettes’ on water

New type of high-speed combat vessel garners high praise despite early problems prompting some ongoing concerns

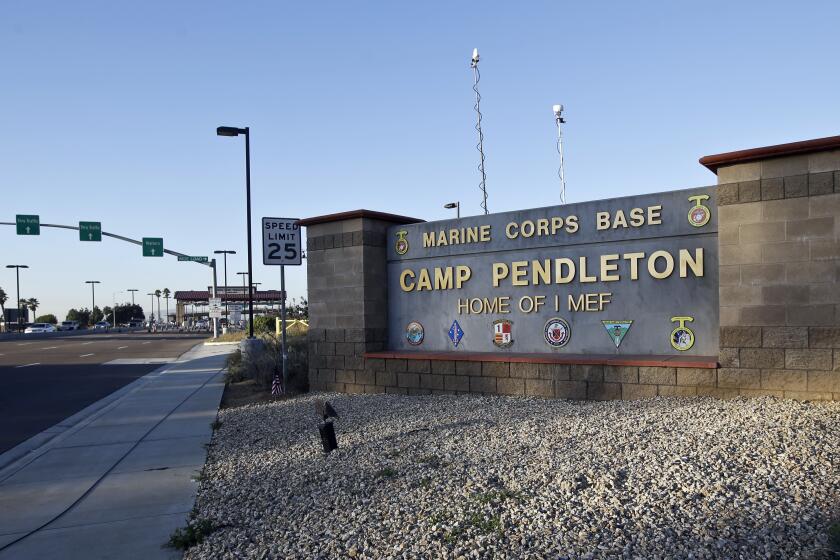

Command Master Chief Clayton Hartley didn’t mince words as he stepped through the passageways of Fort Worth, a San Diego-based littoral combat ship (LCS) that’s gearing up for its first major deployment.

“No other ship in the Navy handles like this; we’re a corvette,” said Hartley, “And we’re fast. Put down the throttle and this boat will thrown you back in your seat.”

Hartley was expressing rarely heard praise for the LCS, a new type of high speed vessel that’s designed to zip around shallow near=shore waters on missions ranging from minesweeping to hunting submarines to small-scale surface warfare.

The concept for the ship grew out of simulated war games in the 1990s. Naval planners played out scenarios set in the Straits of Hormuz and began to envision a comparatively inexpensive, stealthy replacement for aging frigates, minesweepers and patrol boats.

The idea matured into the LCS program, which got underway in late 2001 amid doubts inside and outside the Navy that this was the kind of “streetfighter” that was needed. There was particular concern about turning LCS into about one-sixth of an eventual 305-ship Navy.

Littoral combat ship, Freedom class

These monohulls will focus on surface warfare, minesweeping and anti-submarine warfare.

Length: 378 feet

Crew: Up to 78

Displacement: 3,000 tons

Speed: 40-plus knots

Armament: One 57 mm gun,2 Bushmaster 30 mm guns, Rolling Airframe Missiles

2

1

Littoral combat ship, Independence class

A high-speed vessel designed to enter shallow, near-shore waters to do everything from minesweeping to hunting for submarines.

Length: 418 feet

Crew: Up to 78

Displacement: 3,104 tons

Speed: 40-plus knots

Armament: Hellfire missiles,one 57 mm gun, four .50-caliber guns, anti-ship guns

2

1

Those concerns haven’t eased even though the first four LCS have arrived in San Diego, the epicenter of testing for the new vessel. In fact, the concerns have grown into frustration, anger and impatience, some of it coming from the Navy.

The cost of the two classes of LCS — Freedom and Independence — has started to decline after the first four turned out to be budget busters. But government and defense analysts say the entire program has been marred by everything from delays to poor design to spotty construction and finicky propulsion systems.

The problems have generated many questions, including: Are the ships too fragile? Are they too lightly armed. Are they as stealthy as advertised? Can crews swap out mission equipment in a reasonable amount of time? Are their crews too small?

In February, the doubts led Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel to cut planned construction of LCS vehicles by 20, to the 32-34 range. He also told defense contractors to evaluate whether the Navy needs a more lethal LCS, or a new generation of frigates.

Christine Fox, acting deputy Defense Secretary, backed Hagel, saying the Navy needs fewer “niche platforms.”

The problems led Jonathan Greenert, chief of naval operations, to say that the Navy has failed to clearly explain how LCS will evolve over time.

Vice Admiral Tom Copeman, commander of Naval Surface Forces, Pacific Fleet, said, “Most of the issues involving the hulls of these ships have already been worked out, and I’m confident that any issues with them mission packages they carry will be, too.”

It does not appear that the program will be cancelled -- over the short time. An additional four LCS are in various phases of construction and are scheduled to arrive in San Diego over the next two years. And canceling the program could be unwise, says the Congressional Budget Office, which published a highly critical review of LCS last fall. The review says:

“Canceling the LCS program would have several disadvantages ... Both variants of the LCS represent innovative additions to the future force at a price much lower than that of other shipbuilding programs, and thus far no alternatives have been put forth that could perform its three types of missions more effectively and at a lower cost. Virtually every new class of surface combatant over the past 30 years—Spruance destroyers, Oliver Hazard Perry frigates, Ticonderoga cruisers, and Arleigh Burke destroyers— was initially criticized over its capabilities and costs but, when the construction was finished and the problems fixed, was regarded as a valuable component of the Navy’s fleet.

“Also, the ship’s sea frame (the ship itself) and interchangeable mission packages give it considerable flexibility to adapt as the security environment evolves over the ship’s 25-year service life. In addition, canceling the program would not eliminate the missions the LCSs would be needed to perform; other existing ships or newly designed ships would have to perform any missions that the 24 LCSs could not.

“Moreover, in an era of tight funding, the LCS represents a relatively inexpensive way to increase the fleet’s size to reach the Navy’s goal of more than 300 ships. Although the LCS may not be able to perform some missions as effectively as larger and more-expensive ships, it is a key component of the Navy’s planned force structure: The Navy will be able to make use of the ships for maritime security operations and other, noncore missions such as engagement with allies. At $550 million, the average cost of an LCS with a mission package is one-third as expensive as an Arleigh Burke destroyer and cheaper than what it would cost to build a new Oliver Hazard Perry frigate today.

If LCS has a future, it will largely be based on what happens over the next couple of years with ships operating out of San Diego. Ships like the Fort Worth.

Hartley likes the odd, saying, “Once sailors cycle through and get to know these ships, they’ll find that they like them.”

Shipbuilding and quality control

Littoral combat ships have received so much bad publicity it’s obscured the fact that many types of ships experience serious design, construction and operation problems, some which can make a vessel unseaworthy. The nonpartisan Government Accountability Office, or GAO, published a review of Navy shipbuilding last year that highlighted the defects, many which involved ships now operating out of San Diego.

In particular, the GAO expressed concern about the quality of San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock ships, 684-foot vessels that carry Marines, vehicles, and a large complement of aircraft. The San Diego had almost 4,800 important deficiencies when the contractor delivered it to the Navy. It’s sister ship, Anchorage, had 1,270. GAO says the most serious problems with the San Antonio-class ships ranged from bad welds that could cause oil to leak, seizing up the engine, to a failure to the use the right materials in the exhaust system.

Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, which are known as the workhorse of the Navy because they can perform so many different types of missions, also got dinged in the GAO report.

“Despite being a well established program, the Arleigh Burke class continues to have a large number of open deficiencies at various points in time,” says the GAO report, whose review included the San Diego-based destroyers Wayne E. Meyer, Dewey, William P. Lawrence and Spruance. The class-wide defects ranged from poor wiring and welding, to spotty paint jobs that made the ships more susceptible to costly rusting.

The GAO also found serious problems with the gas turbines and piping on the Makin Island, a San Diego-based amphibious assault ship.

Most of the problems were corrected before the ships began significant operations. But GAO analysts said both the Navy and its contractors have to do a far better job on the basics of shipbuilding.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.